Post by Jon Doeman on Oct 30, 2013 13:26:50 GMT

The forgotten story of ... Alec Stock | Simon Burnton | Sport | theguardian.com

"It is possible that before you finish this book another manager of a football league club will be sacked. A lot of people will shake their heads knowingly and the fact will be dutifully reported in the newspapers, but unless the manager's name is a household word, nobody will get very excited. Why should they? One does not get excited because night follows day, and failure in league football is followed by the manager's head with the same unfailing regularity ... This may be harsh, it may be sad and to many managers it is certainly frightening, but it is also inevitable. Managers need success like other men need food and drink, but regrettably not all 92 of them can win something every season."

So begins Football Club Manager, Alec Stock's brilliantly readable treatise on life in the hotseat. It was a dispassionate assessment of his trade by a man who, when the book came out, had been in management for 21 years without getting the sack. If success was indeed to managers what food and drink was to other men he was in the middle of a feast of truly epic proportions, but within a year, the taste of dessert still on his lips, he was to be at the receiving end of possibly the harshest booting-out in the history of British football.

Having played a bit for QPR before the second world war Stock first came to the football world's attention when as player-manager he guided Yeovil, then of the Southern League, to the fifth round of the FA Cup in 1949, beating Bury when they were first in the Second Division and Sunderland when they were second in the First – when Stock himself, never the most accomplished player and hampered by shrapnel lodged in his leg and buttock after his wartime service in the tank corps, scored a stunning and entirely atypical left-foot volley from the edge of the area.

His burnished reputation survived an 8-0 drubbing at Old Trafford in round five, and he soon moved to Leyton Orient, where he returned after brief dalliances with Arsenal (53 days as assistant and heir apparent to Tom Whittaker, before he was asked to spend a Saturday watching Aldershot's reserves rather than Arsenal's first-team and he left) and Roma (11 matches, only one of them lost, before the directors told him who to put in the team and he left) and whom he led to promotion in 1956. Two years after that he joined QPR.

Though Stock initially did reasonably well, the club's accounts did not and the board was soon left with no choice but to urgently seek investment. In 1965, Jim Gregory arrived as chairman, and changed the club for ever. Having started as a market fishmonger the brash, abrasive Gregory had graduated to selling used cars, then new cars, then garages, and then entire chains of garages. He was a man accustomed to success, determined to savour more of it at Loftus Road and prepared to dip into his own pocket to guarantee it.

"Jim was a very difficult man to work with," Ron Phillips, QPR's secretary between 1966 and 1989, tells me. "He wasn't like Alec at all. Alec's nickname was 'the first gentleman of soccer'. He was a very nice man and a gentleman in every way. Jim Gregory was precisely the opposite. He was a terribly impatient man, and wanted success immediately."

Fortunately, he got it. His first full season ended with the club third, one place if eight points from promotion. Towards the end of it he funded the signing of Rodney Marsh from Fulham for £15,000 – Stock repeatedly plundered Fulham's reserves, later finding Malcolm Macdonald from the same source. "It is no secret that I have always preferred London players," he wrote. "I know and trust them and feel happiest working with them". The brilliant young forward scored 44 times in all the following season, which ended with QPR winning the league by 13 points (and this in the days of two points for a win). They also reached the League Cup final, which for the first time that year was played at Wembley, and came back from a 2-0 half-time deficit against First Division West Bromwich Albion to become the first third-tier side to win there. The trophy was kept in a bank vault, because QPR didn't possess a trophy cabinet. They had never really needed one.

Winning back-to-back promotions to storm into the top flight is a rare feat today, but back then it simply was not done. Only one team had achieved it before, and that was more than 30 years earlier. But QPR won five of their first six games and were never out of the top two, though the prize was very nearly plucked from their grasp at the death. Blackpool were level with them on the final day after a six-game winning run, and their players celebrated on the pitch as they extended it to seven while Rangers were only drawing at Aston Villa. Meanwhile, at Villa Park, a late own-goal gifted QPR a 2-1 victory and promotion on goal average. "Everyone in the dressing-room afterwards was shattered," Stock said. "I was a wreck, drained of everything except happiness."

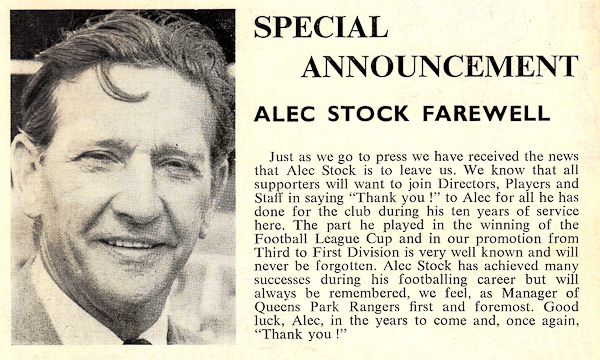

It was his last match as QPR manager. What Stock had achieved – taking a club that had spent all but four seasons of their history in or below the Third Division to two promotions and what remains their only major trophy – ranks alongside the greatest achievements in lower-division football management, but Gregory was already attempting to manoeuvre him out of the club. Over the summer he tried to prompt a resignation, criticising his every move and briefing the press that Stock was to be stripped of control over first-team affairs and assume the title general manager.

"Jim felt Alec couldn't bring any more successes and he really wanted him out," Phillips tells me. "He started making his life very difficult." In his unpublished memoir, Phillips recalls "constant complaints about the way the team were playing and nonstop criticism of Alec's administrative decisions". And just as Gregory sought an excuse to banish Stock, fate gave him one.

Three days after the 1967 League Cup final QPR beat Bournemouth 4-0 at home, an increasingly familiar display of attacking brio from a side on a run that saw them score 23 goals and concede two in 10 league matches. Marsh scored a couple, and would later declare it the finest performance of his career. Leaving the ground after the game, Stock became unexpectedly breathless. It was his first asthma attack.

"My asthma was caused and then aggravated, the experts say, by years of shouting and screaming at players during training," he wrote in his autobiography, A Thing Called Pride, which was published in 1981. "It was a real struggle to get through the remainder of our promotion season, and even harder when we went up to the First Division. There were many days when I had to hide my condition from the players and I remember coming home from floodlit matches and just sitting up all night."

Stock's youngest daughter, Sarah, doesn't remember the asthma being particularly debilitating. "He'd never had problems with it as a player," she says. "He'd served in the army in world war two, and as far as I'm aware there was never any issue with it. But that summer I remember I was packed off to Somerset to my grandmother's farm. I kept saying I wanted to go home, and they kept making excuses why I had to stay. What I didn't know was that dad was up in chest hospitals. But most of the time he was at home relaxing. Everything was fine, he was just recuperating."

On medical advice, Stock took three months' leave in the summer of 1968. In his absence QPR faltered, winning only two of their first 17 league fixtures before their manager returned to work that November. "I knew that Jim Gregory would be at the ground," he wrote. "'I want to see you a minute Alec,' he said. I thought he was going to welcome me back with open arms. I thought and hoped he was going to say, 'Come on Alec, glad to have you back, let's get this show on the road again.' But he didn't, and 20 seconds later I was out, sacked, with this damning testimony. 'You are ill, you're incurable, I want you to go.'" Stock later said he had been "treated as though I had pinched the petty cash".

Though in many ways the writing had been on the wall, Stock was genuinely astonished by the sacking. "I just remember the atmosphere at home, being shell-shocked," Sarah says. "I was only three when Dad went to Rangers. I grew up there, I used to hang out there, babysit for the players and go to their weddings. It was just total shock. It was Dad's dream to pick a First Division side, he couldn't understand why they were losing and he had been desperate to get back."

Gregory's family used to socialise with the Stocks. They would buy each other Christmas presents. "Dad got on well with Jim Gregory for a long time. It was all very amenable, but then things just changed very quickly," Sarah says. "Elizabeth [Stock's older daughter] remembers going to the first game in the First Division, and suddenly Tommy Docherty was sitting in the stands. This was before dad had got the sack. Obviously there were things going on behind the scenes."

The club released a terse statement, saying Stock's departure had been "amicably agreed by mutual consent", but journalists were told that Stock was too sick to work. Stock proved them wrong by moving back to the Third Division with Luton six weeks later, and he was to work for another 12 years, bringing the Hatters to promotion and Fulham to an FA Cup final, and live for 33. "He lived with me for the last 10 years of his life, and in his 70s he was still coming to the gym with me and going training, and running my son ragged," Sarah says. Docherty replaced him at QPR, but quit after 28 days having fallen out with Gregory (not for the last time – Docherty returned in 1979, was sacked in May 1980, rehired nine days later and sacked again that October). "When you shook hands with him, you counted your fingers," Docherty said of Gregory. "He was a crook."

Some 10 years after Stock's sacking, Phillips remembers Gregory bringing him up in conversation. "I was sitting in his office when he suddenly said, 'You know my big mistake, Ron? I should never have let Alec go,'" he recalls. "It was the only time I heard him admit to a mistake." Stock was invited back to the club as a director, and briefly retook control of the team as caretaker manager. "It seemed like a good idea at the time," Stock wrote. "I'm sure Jim asked me back to clear his conscience from all those years before, but it was probably the wrong decision." He considered his time in the boardroom "a bloody awful job shaking hands and pouring gin and tonics" and left when Bournemouth offered him what was to be his last job in management, at the age of 62.

But QPR were to be guilty of mistreating Stock again. Though he played for the club before the war, spent a decade there as manager, brought them unparalleled success and later returned to the board, when he grew old and unwell they turned their back. In 1999, two years before his death, Yeovil arranged a testimonial to fund his care but QPR refused to help; after his death they threw a dinner in his honour and again Rangers stayed away. "When my dad was ill, Yeovil and Fulham were the ones who came through," Sarah recalls. "Rodney Marsh and a few players came back, but it was very much Fulham and Yeovil who tried to help."

When Gregory bought the club in 1964 it was in the Third Division, financially imperilled and with a small and ramshackle stadium. When he left it was in the First Division, financially secure and with a totally renovated ground. That the club is where it is today, or that it exists at all, is down in large part to his support, but his treatment of the man who first led QPR to the top flight was every bit as shabby as the rickety old stands he replaced. Stock's wife, Marjorie, once conjured a memorable description of her husband's time at Loftus Road: "He climbed the mountain, and found rubbish at the top."

www.theguardian.com/sport/blog/2013/oct/30/forgotten-story-alec-stock-qpr-manager

"It is possible that before you finish this book another manager of a football league club will be sacked. A lot of people will shake their heads knowingly and the fact will be dutifully reported in the newspapers, but unless the manager's name is a household word, nobody will get very excited. Why should they? One does not get excited because night follows day, and failure in league football is followed by the manager's head with the same unfailing regularity ... This may be harsh, it may be sad and to many managers it is certainly frightening, but it is also inevitable. Managers need success like other men need food and drink, but regrettably not all 92 of them can win something every season."

So begins Football Club Manager, Alec Stock's brilliantly readable treatise on life in the hotseat. It was a dispassionate assessment of his trade by a man who, when the book came out, had been in management for 21 years without getting the sack. If success was indeed to managers what food and drink was to other men he was in the middle of a feast of truly epic proportions, but within a year, the taste of dessert still on his lips, he was to be at the receiving end of possibly the harshest booting-out in the history of British football.

Having played a bit for QPR before the second world war Stock first came to the football world's attention when as player-manager he guided Yeovil, then of the Southern League, to the fifth round of the FA Cup in 1949, beating Bury when they were first in the Second Division and Sunderland when they were second in the First – when Stock himself, never the most accomplished player and hampered by shrapnel lodged in his leg and buttock after his wartime service in the tank corps, scored a stunning and entirely atypical left-foot volley from the edge of the area.

His burnished reputation survived an 8-0 drubbing at Old Trafford in round five, and he soon moved to Leyton Orient, where he returned after brief dalliances with Arsenal (53 days as assistant and heir apparent to Tom Whittaker, before he was asked to spend a Saturday watching Aldershot's reserves rather than Arsenal's first-team and he left) and Roma (11 matches, only one of them lost, before the directors told him who to put in the team and he left) and whom he led to promotion in 1956. Two years after that he joined QPR.

Though Stock initially did reasonably well, the club's accounts did not and the board was soon left with no choice but to urgently seek investment. In 1965, Jim Gregory arrived as chairman, and changed the club for ever. Having started as a market fishmonger the brash, abrasive Gregory had graduated to selling used cars, then new cars, then garages, and then entire chains of garages. He was a man accustomed to success, determined to savour more of it at Loftus Road and prepared to dip into his own pocket to guarantee it.

"Jim was a very difficult man to work with," Ron Phillips, QPR's secretary between 1966 and 1989, tells me. "He wasn't like Alec at all. Alec's nickname was 'the first gentleman of soccer'. He was a very nice man and a gentleman in every way. Jim Gregory was precisely the opposite. He was a terribly impatient man, and wanted success immediately."

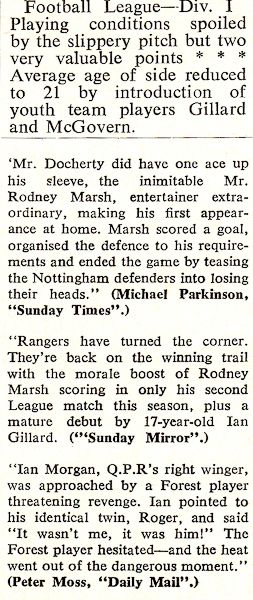

Fortunately, he got it. His first full season ended with the club third, one place if eight points from promotion. Towards the end of it he funded the signing of Rodney Marsh from Fulham for £15,000 – Stock repeatedly plundered Fulham's reserves, later finding Malcolm Macdonald from the same source. "It is no secret that I have always preferred London players," he wrote. "I know and trust them and feel happiest working with them". The brilliant young forward scored 44 times in all the following season, which ended with QPR winning the league by 13 points (and this in the days of two points for a win). They also reached the League Cup final, which for the first time that year was played at Wembley, and came back from a 2-0 half-time deficit against First Division West Bromwich Albion to become the first third-tier side to win there. The trophy was kept in a bank vault, because QPR didn't possess a trophy cabinet. They had never really needed one.

Winning back-to-back promotions to storm into the top flight is a rare feat today, but back then it simply was not done. Only one team had achieved it before, and that was more than 30 years earlier. But QPR won five of their first six games and were never out of the top two, though the prize was very nearly plucked from their grasp at the death. Blackpool were level with them on the final day after a six-game winning run, and their players celebrated on the pitch as they extended it to seven while Rangers were only drawing at Aston Villa. Meanwhile, at Villa Park, a late own-goal gifted QPR a 2-1 victory and promotion on goal average. "Everyone in the dressing-room afterwards was shattered," Stock said. "I was a wreck, drained of everything except happiness."

It was his last match as QPR manager. What Stock had achieved – taking a club that had spent all but four seasons of their history in or below the Third Division to two promotions and what remains their only major trophy – ranks alongside the greatest achievements in lower-division football management, but Gregory was already attempting to manoeuvre him out of the club. Over the summer he tried to prompt a resignation, criticising his every move and briefing the press that Stock was to be stripped of control over first-team affairs and assume the title general manager.

"Jim felt Alec couldn't bring any more successes and he really wanted him out," Phillips tells me. "He started making his life very difficult." In his unpublished memoir, Phillips recalls "constant complaints about the way the team were playing and nonstop criticism of Alec's administrative decisions". And just as Gregory sought an excuse to banish Stock, fate gave him one.

Three days after the 1967 League Cup final QPR beat Bournemouth 4-0 at home, an increasingly familiar display of attacking brio from a side on a run that saw them score 23 goals and concede two in 10 league matches. Marsh scored a couple, and would later declare it the finest performance of his career. Leaving the ground after the game, Stock became unexpectedly breathless. It was his first asthma attack.

"My asthma was caused and then aggravated, the experts say, by years of shouting and screaming at players during training," he wrote in his autobiography, A Thing Called Pride, which was published in 1981. "It was a real struggle to get through the remainder of our promotion season, and even harder when we went up to the First Division. There were many days when I had to hide my condition from the players and I remember coming home from floodlit matches and just sitting up all night."

Stock's youngest daughter, Sarah, doesn't remember the asthma being particularly debilitating. "He'd never had problems with it as a player," she says. "He'd served in the army in world war two, and as far as I'm aware there was never any issue with it. But that summer I remember I was packed off to Somerset to my grandmother's farm. I kept saying I wanted to go home, and they kept making excuses why I had to stay. What I didn't know was that dad was up in chest hospitals. But most of the time he was at home relaxing. Everything was fine, he was just recuperating."

On medical advice, Stock took three months' leave in the summer of 1968. In his absence QPR faltered, winning only two of their first 17 league fixtures before their manager returned to work that November. "I knew that Jim Gregory would be at the ground," he wrote. "'I want to see you a minute Alec,' he said. I thought he was going to welcome me back with open arms. I thought and hoped he was going to say, 'Come on Alec, glad to have you back, let's get this show on the road again.' But he didn't, and 20 seconds later I was out, sacked, with this damning testimony. 'You are ill, you're incurable, I want you to go.'" Stock later said he had been "treated as though I had pinched the petty cash".

Though in many ways the writing had been on the wall, Stock was genuinely astonished by the sacking. "I just remember the atmosphere at home, being shell-shocked," Sarah says. "I was only three when Dad went to Rangers. I grew up there, I used to hang out there, babysit for the players and go to their weddings. It was just total shock. It was Dad's dream to pick a First Division side, he couldn't understand why they were losing and he had been desperate to get back."

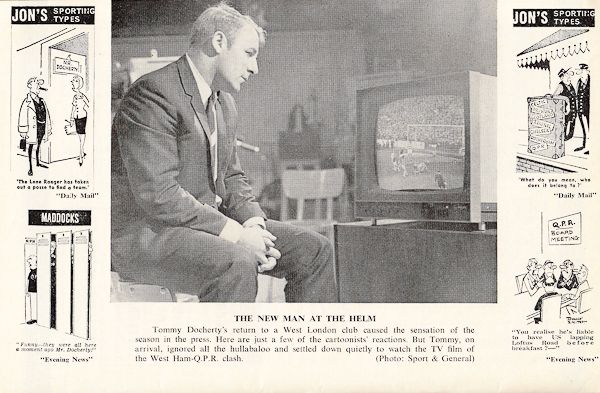

Gregory's family used to socialise with the Stocks. They would buy each other Christmas presents. "Dad got on well with Jim Gregory for a long time. It was all very amenable, but then things just changed very quickly," Sarah says. "Elizabeth [Stock's older daughter] remembers going to the first game in the First Division, and suddenly Tommy Docherty was sitting in the stands. This was before dad had got the sack. Obviously there were things going on behind the scenes."

The club released a terse statement, saying Stock's departure had been "amicably agreed by mutual consent", but journalists were told that Stock was too sick to work. Stock proved them wrong by moving back to the Third Division with Luton six weeks later, and he was to work for another 12 years, bringing the Hatters to promotion and Fulham to an FA Cup final, and live for 33. "He lived with me for the last 10 years of his life, and in his 70s he was still coming to the gym with me and going training, and running my son ragged," Sarah says. Docherty replaced him at QPR, but quit after 28 days having fallen out with Gregory (not for the last time – Docherty returned in 1979, was sacked in May 1980, rehired nine days later and sacked again that October). "When you shook hands with him, you counted your fingers," Docherty said of Gregory. "He was a crook."

Some 10 years after Stock's sacking, Phillips remembers Gregory bringing him up in conversation. "I was sitting in his office when he suddenly said, 'You know my big mistake, Ron? I should never have let Alec go,'" he recalls. "It was the only time I heard him admit to a mistake." Stock was invited back to the club as a director, and briefly retook control of the team as caretaker manager. "It seemed like a good idea at the time," Stock wrote. "I'm sure Jim asked me back to clear his conscience from all those years before, but it was probably the wrong decision." He considered his time in the boardroom "a bloody awful job shaking hands and pouring gin and tonics" and left when Bournemouth offered him what was to be his last job in management, at the age of 62.

But QPR were to be guilty of mistreating Stock again. Though he played for the club before the war, spent a decade there as manager, brought them unparalleled success and later returned to the board, when he grew old and unwell they turned their back. In 1999, two years before his death, Yeovil arranged a testimonial to fund his care but QPR refused to help; after his death they threw a dinner in his honour and again Rangers stayed away. "When my dad was ill, Yeovil and Fulham were the ones who came through," Sarah recalls. "Rodney Marsh and a few players came back, but it was very much Fulham and Yeovil who tried to help."

When Gregory bought the club in 1964 it was in the Third Division, financially imperilled and with a small and ramshackle stadium. When he left it was in the First Division, financially secure and with a totally renovated ground. That the club is where it is today, or that it exists at all, is down in large part to his support, but his treatment of the man who first led QPR to the top flight was every bit as shabby as the rickety old stands he replaced. Stock's wife, Marjorie, once conjured a memorable description of her husband's time at Loftus Road: "He climbed the mountain, and found rubbish at the top."

www.theguardian.com/sport/blog/2013/oct/30/forgotten-story-alec-stock-qpr-manager

Thanks for that.

Thanks for that.