Flashback to (Trying to) Playing for Ireland

The Sunday Times - 2004

March 21, 2004

Gallen’s call stirs IrelandHis brothers played for Ireland while he chose England, but now Kevin Gallen has told Brian Kerr he wants to wear greenjohn o'brien The scene is an Irish club in Acton, west London. It is June 2002 and on the big screen Ireland and Spain are set to lock horns in the last 16 of the World Cup. The bar is a sea of green flags and painted faces. The atmosphere is charged and electric, the mood expectant. The Gallen family sit among them, proud and happy and Irish.

Stephen Gallen waves his scarf in the air and casts a reproachful glare at one of his companions across the table. “How could you be shouting for Spain?” he scolds, waving a finger in his brother Kevin’s direction. Kevin Gallen stares back in outrage. “There’s no need to be saying that to me,” he complains. “Why would I want Spain to beat Ireland?” He knows protests are futile. They always have been. It’s 11 years since Gallen, the product of an intensely Irish upbringing, accepted the invitation to play for England and forfeited, in many eyes, any rights he had to consider himself an Irishman. Protesting his innocence has always been a pointless exercise. Context and circumstance were luxuries that the narrow-minded interpretation of his case never allowed.

What had always been a complex and contentious issue was, in Gallen’s case, reduced to convenient clarity. He was a traitor and a turncoat, deserving of our scorn. Mocked by many journalists and Ireland supporters, some friends and even members of his own family. Nothing he could say, he felt, would ever change it.

All he ever hoped for was a time when he could return to Ireland, have a drink in his uncle’s pub in Mayo and not have a local remind him of his treachery. He never believed it would happen. But he never imagined that his story would take the strange twist that it has.

It happened in November. A man from County Limerick sent him a letter pointing out a rule change by Fifa that enabled players capped by one country at under-age level to switch their allegiance to another. He read and re-read the letter and was intrigued by its contents but wary too. Would the Irish people accept him? Was he merely setting himself up for a hard and painful fall? He talked to people: his parents and brothers, Gary Waddock, youth coach at QPR, a friend in the Republic of Ireland supporters club in London. The feedback was reassuring. He thought about going to the press but balked at the inevitable “Come and get me” headlines. Instead he wrote a letter setting out his story and sent it to Brian Kerr. Encouragingly, Kerr wrote back.

“He sent me a very nice letter,” Gallen says. “I appreciated that. It wasn’t something he had to do. He said he was sympathetic to my case but wasn’t able to make any promises. I understand that. But he’s been to see me play and I know the door isn’t completely closed.”

Whatever happens, Gallen knows, it is a chance he had to take, an opportunity to heal old wounds. To represent Ireland like his two brothers did before him, to put an Irish cap alongside the English ones on the sideboard in a house where his parents are equally proud of all their sons. What, he thinks, is there to lose? “I could get more abuse. I could be called a traitor again. I’m well used to it. I’ve had it all and I could handle it again.”

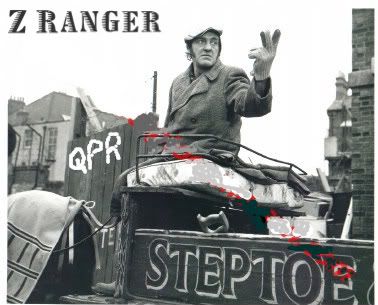

THEY were a typical Irish family growing up in west London. Jim left his native Donegal in the 1960s and ended up on the buildings in Shepherd’s Bush. Tess left Mayo around the same time and ended up in the same area via a spell in America. They met in an Irish pub, married and raised a family of three boys and two girls to love Ireland and Queens Park Rangers.

The boys’ school was the Cardinal Vaughan Memorial in Holland Park. Their social life revolved around the Acton and Ealing Whistlers, the Irish music club Jim and Tess helped set up as a focal point for the Irish community.

The Whistlers also fielded seven or eight soccer teams who wore the Irish green. The Gallen brothers were the stars.Kevin was so talented he played on the same team as Joe, three years his senior. Jim was their manager.

Watford would come looking for Joe, and QPR for Kevin when he was 14. England schoolboys was the next step. That didn’t mean much in terms of national fealty. In 1992 Joe made his debut for the Ireland under-21s; that Kevin would follow in his footsteps was accepted as a formality.

But neither Joe nor Steve, who would play for the Ireland youths in 1994, were quite like their brother. Kevin was a teenage sensation, the most talked about young striker in England apart from Robbie Fowler. In two seasons in the QPR youth team he knocked in more than 130 goals and in the spring of 1993 the English FA came calling, enlisting him for the European under-18 championship finals that summer.

The loss to Ireland, a country with a chronic shortage of quality strikers, was inestimable. Inevitably it magnified the extent of Gallen’s perceived crime. He says vehemently that nobody from the FAI ever approached him directly. In the middle of the Charlton years, when the approach to youth football was feckless, that is well believable.

At the time Joe McGrath, the FAI’s national director of coaching, said he had been aware of Gallen since the turn of the decade. “Somebody at QPR was absolutely determined that Kevin should opt for England,” McGrath explained. Gallen tells a similar, more detailed story.

“What I said in my letter to Brian was that I didn’t know whether contact had been made between the FAI and QPR but nobody from the FAI spoke to me directly. I knew they had to be aware of me through my brothers but I was never told of any approach. Maybe I could have taken a step back and thought about the consequences but when you’re a kid you don’t think much about the future. It’s all about the here and now.”

And that’s only half the story. The three-foreigner rule was then in place and QPR didn’t need a Republic of Ireland international on their books. He remembers people at the club who were disparaging of the idea of playing for Ireland. “People who wouldn’t call it Ireland,” he says, “but refer to it as Eire, you know, in a joke sort of way.”

QPR wanted him but their interest was conditional. A new four-year contract with gob-smacking bonuses was waved in front of him, hinging on one crucial detail. “It all hung on whether I played for England. It was all England, England, England. Ireland was never mentioned. Ireland didn’t enter the equation as far as they were concerned.”

His situation has always been compared with that of other Irish players, usually to compound his guilt. It’s been reported that Kevin Kilbane withstood pressure at Preston to declare for England, as if Kilbane was a similarly talented prodigy, as if he had suffered the same overbearing influence.

History was not to be Gallen’s friend. His goals would help England win that European under-18 championship. Fowler, Gary Neville, Paul Scholes and Sol Campbell were among his teammates. After that a senior debut for QPR would follow at Old Trafford and his first senior goal at Loftus Road a few days later. But people in Ireland don’t remember that now. They recall only one thing.

“When I come to Ireland I get it all the time,” he says. “‘Why didn’t you play for Ireland? Why? Why?’ If I’m with family and I go to my uncle’s pub somebody will bring it up and I’m like, ‘Oh for f*** sake. It’s gone. I can’t do anything about it now’.”

Nor did his family grant him immunity. “I get it off my two brothers. We get on very well but they take this very seriously, especially Steve. He’s very patriotic and I know he’d be delighted if I got the chance to play for Ireland.”

As luck would have it one of his four England under-21 caps came against Ireland at Lansdowne Road in March 1995. He was sitting in the dressing room when he heard his name announced followed by loud hoots of derision. “It was a hard day. Little kids coming up to me and effing and blinding me. I don’t think it was nice for my parents in the stands. I tried to laugh it off. What else could I do?” He never got a senior cap for England. He knows there are those who feel justice was served, that karma prevailed. The pressure of being a starlet didn’t help, neither did a cruciate ligament injury in August 1996. Only now, he thinks, is he approaching the form that earned him such a lavish reputation.

He’s blunt about his situation, though. He knows Ireland are short of strikers and feels he could do a job as a foil for Robbie Keane, but while he has scored 16 goals for QPR this season and played as well as ever, they are still in Division Two and he will be 29 in September. If Kerr passes him over for football reasons he will understand.

“I can see that point of view,” he says. “I know for a fact a lot of people would not be happy to see me in the Ireland squad. But then a lot of people would be happy, too. Everybody’s got an opinion. You can’t please everyone. I understand, too, if he wants to bring youngsters through. But at the end of the day it’s about getting results and I feel the way I’m playing at the moment I can help.”

No illusions. He’s neither apologising nor playing the victim’s card, he’s just explaining and asking for compassion. He only has hope. “A part of me is preparing for the worst,” he says. “People telling me to go away, to f*** off. I know that’s a possibility.”

But maybe, just maybe, in the months ahead the one person who matters might come whistling a different tune.

www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/sport/football/article1049707.ece?token=null&offset=12&page=2